During the week, Hala Targowa market in Kraków is an open-air area to buy fruit, vegetables, meat and cheese. But on Sundays it transforms into a flea market. Between professional antique dealers and second hand book traders, old men and women bring objects from their apartments and houses and lay them out on the ground to sell.

The objects come, often, from the communist era: slide projectors, plates, clocks, lamps, clothing, ancient calculators. Such objects hold a certain fascination, coming from a different time, with its own aesthetics and values. Hala Targowa can start to look like a museum. Every object has a story, often connected to the person who sells it to you. These are stories forever closed off to the buyer. You can only imagine.

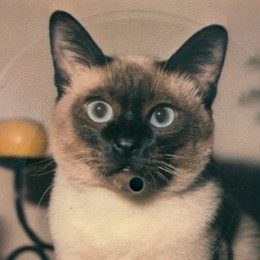

Mat Schulz tells his Sound Postard story Among other objects I found, one day, a square postcard image of a cat, upon which had been printed the vinyl tracks of a record. I turned the card over. The song was Dance Kung Fu and Love Peace and Happiness (sic!) by C. Douglas. The image and the song had no connection at all, which made the artifact even more curious. Although there was a place to write an address and stick a stamp, it had never been sent.

Mat Schulz tells his Sound Postard story Among other objects I found, one day, a square postcard image of a cat, upon which had been printed the vinyl tracks of a record. I turned the card over. The song was Dance Kung Fu and Love Peace and Happiness (sic!) by C. Douglas. The image and the song had no connection at all, which made the artifact even more curious. Although there was a place to write an address and stick a stamp, it had never been sent.

It was a Pocztówka Dźwiękowa – which translates as Sound Postcard.

In the months that followed I kept returning to Hala Targowa, and my eyes became more keenly peeled, looking for Pocztówki Dźwiękowe amongst the other debris. The cards were rarely sold by mainstream antique dealers; rather, it was those working at the periphery of the market who had them.

Although similar objects existed elsewhere, I later found out that in communist Poland sound postcards were incredibly popular – an indication of the strong desire Poland had to connect with The West via music. They had their heyday in the 1960s and 1970s when it was difficult to buy real vinyl. People would purchase these cards and take them home to play on portable record players. The most popular type of player was the Bambino, manufactured by the Unitra-Fonica company. When it opened up the case functioned as a speaker, which was connected to the player.

One of the interesting things about Pocztówki Dźwiękowe is that it seems they were hardly ever sent – at least, this is what the lack of stamped and addressed postcards suggests. They were, very often, collected, just as almost all people once made vinyl and cassette collections.

I showed some sound postcards to graphic designer Rui Silva, and we began collecting them together. In the beginning we would buy anything. Later we became more selective. At this point, we bought cards on the basis of their design. The song was secondary.

We also spoke to our Polish friends about Pocztówki Dźwiękowe. The younger ones often had no idea what we were talking about. For them, these cards, that a few decades before had been so popular, had faded into obscurity. Older Poles smiled, or laughed, saying that probably they had some cards in their house somewhere, and would give them to us. Few people found the cards unique.

Neither Rui nor I had turntables at this time, and for many months the cards were simply visual objects to us. Then came a day when, after one Hala Targowa expedition, we were sitting in a Kraków café that had an old record player. We asked if we could listen to a Pocztówka Dźwiękowa. The young waitress was one of those Poles who had never seen one of these cards before, but she put it on. The card, suddenly, came to life, revealing what its apparent purpose was, the reason for its existence: to play music.

The quality, of course, was bad. It was mono, filled with ghostly crackles, hisses and pops, but still, the song was audible, by the so-called Polish version of The Beatles, Czerwony Gitary. The other clients looked around, to see what this faint version of a song was. In response, the waitress took the card off.

Later on we bought Bambino record players. The Bambino 4, produced in the early 70s, has become our preferred model. The problem is that these portable players were not built to last, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to find one that works as it should. As they belong to another era, replacement parts are impossible to find, and already a well functioning Bambino is a rare treasure.

Records in general are in many ways a thing of the past, hoarded by obsessive collectors and DJs. Only a few vinyl pressing plants still remain. CDs have been almost entirely replaced by digital music, downloaded onto mp3 players. Albums lose value as complete items. Songs instead become something we have control over, arriving often from the internet’s virtual universe. They become disposable. Record covers lose significance, as these days album artwork needs to be visible on the screen of an iPod. No longer do you walk into someone’s house and search through their music collection. It is nowhere to be seen, as it does not exist in space.

Sound Postcards

at Culture 2.0 in Warsaw

The collection by Mat Schulz and Rui Silva, shown originally at UNSOUND Festival, was exhibited at Level 2.0 of the Culture 2.0: Media-Aware conference in the National Audiovisual Institute in Warsaw (27-29 October, 2011). There will also a “live” performance as Bambino Sound System.

One of the reasons Pocztówki Dźwiękowe draws us towards them is because they are, as technological objects, even more quaint and outdated than records and CDs. They are reminders of old ways of recording music, and also a different time, Polish communism. Therefore, they have double value as cultural artifacts.

But like mp3s, Pocztówki Dźwiękowe also gave the consumer some kind of power over recorded songs, to put them together in different ways. They did not always exist as finished products. It was possible to purchase a postcard in a kiosk, and take it to a special recording booth, several of which existed in Kraków alone. You were able to record a happy birthday greeting to your mother, husband, sister, friend, and follow it with a song by The Beatles, or Nancy Sinatra. You selected the image. You selected the sound. You created the final object.

And those crackling, frail voices, wishing people a happy birthday, or telling them “I love you”, these are embedded in some of the cards as well. Often, in terms of the graphic design, these are the ugliest cards. But, in some ways, they are also perhaps the most special, because, like letters, they are marked with the trace of a real life, of real sentiment, a fragment of someone’s existence.

Like the golden age of Polish cinema posters, of the 50s and 60s, we hope that sound postcards may come to be regarded as art. The current show is one of a series in our attempt to position them as such, in the context of an exhibition space. It is part a long-term project to collect, preserve and archive as many of these cards as possible, on the internet, and eventually in a book form.

As for the Enter Level 2.0 exhibition, part of the process has involved recording all the cards displayed in the form of mp3s. In this way, we leap from a primitive form of recording technology to the latest one. An object in space and time is turned into an intangible file. All those crackles, hisses and pops of the original mono recording are thus brought to the surface. The bad quality of the sound forces us to also become aware of the mp3 itself, as a form of technology that, sooner or later, will also inevitably be replaced by some other way of recording and playing music. But in the moment we listen, keenly, hearing the past and the present rub up against each other, both conflicting and intertwining.