IWO ZMYŚLONY: Slavs and Tatars emerged in 2006. Yet only one year later you exhibit your works in one of the top Parisian boutiques, and now – in Poland. Who are you people?

SLAVS and TATARS: Well, we describe ourselves as a “faction of polemics and intimacies” – this choice of words is important because it reveals our commitment to a certain maximalism, of scope, scale and tone. We try to constantly switch the registers – apply the macro register of polemics to the micro scale of intimate experiences and vice versa.

SLAVS AND TATARS

A collective dedicated to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China, Slavs and Tatars often collide those things we consider opposites, or incompatible, be it Islam and Communism, metaphysics and humour, or pop culture and geopolitics. www.slavsandtatars.com

Too Much Tłumacz, solo exhibition in Raster gallery, Warszawa, till 10 November 2012,

Untimely Stories, group exhibition in Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź including works by Slavs & Tatars, till 2 December 2012.

Both your newest exhibitions – Not Moscow Not Mecca in Secession Vienna and Beyonsense in MoMA – explore the mystical and the sacred rituals of Islam as a vehicle of social change. Would you like it to be read as kind of critique of western consumerism?

I think the critique is something that comes by its own, but what we try to propose is a different way of being. In both of these institutions we created a space to occupy, to contemplate. At the Secession people could take fruits – on the platform were fruits sculptures reflected in the mirror but also real fruits you could take and eat. We wanted another way to engage with the work, not just cerebrally but sensorially.

As for the MoMA, the crowds can sometimes make the museum feel like a train station – some 10 000 people walk through the exhibition spaces every day. It is very busy and very noisy: and that’s a testament to the success of the institution. Yet we would like to offer the opposite – a kind of calm, contemplative, sacred reading space. So we created a big wall of rugs, about 7 meters tall, and when you walk through it, all of the sudden the space is no longer bright, not cold and not loud, but warm and quiet – a kind of psychedelic library space.

It sounds like a typical strategy of institutional critique, wouldn’t you agree?

Not really… we’re not particularly interested in the notion of institutional critique. Too often it’s inward facing, speaking to a restricted audience of art professionals. We prefer to face outwards, in an effort to interest people beyond the art world. Not too mention, we exist thanks to public institutions – without publically-funded art spaces, our publications, exhibitions, conversations, research would not be possible. The reason why we’ve chosen such a name is not only because it sounds funny, but because we are looking at an area that is often overlooked. While the focus is largely on Asia, the Middle East, or Eastern Europe, few people look at the Caucasus or Central Asia – at least in the way we would like it to be considered. Slavs and Tatars looks to redeem a set of beliefs, ideas, thought process, behaviours of a given region, something that many might consider traditional values. Some people even accuse us of being reactionary…

Really?

Sure, among intellectuals, one can only address such thorny issues as faith, religion, and the like with gloves on, analytically, at a distance but not affectively, not experientially, not intimately.

79.89.09. lecture-performance, Triumph Gallery, Moscow, 2011, photo: courtesy of Kolya Zverkov

79.89.09. lecture-performance, Triumph Gallery, Moscow, 2011, photo: courtesy of Kolya Zverkov

Whereas your work focuses on something serious: the political and visual identity of Eurasia…

We would say more the linguistic, emotional and affective understanding of a particular region. In the past three or four years we’ve been trying to go beyond politics to questions of religion, history, anthropology. Politics is too recent – we are too close to it, it doesn’t afford us the distance, the calm, to understand the storm.

Since you’ve identified the western border of Eurasia as the line of the former Berlin Wall, have you thought about projects concerning the identity of Eastern Germans? Ethnically, most of them aren’t Slavs, but they used to live in a communist country, in fact – in some ways even more totalitarian than Poland used to be.

We would like to, since for us it is part of an emotional territory that we are dealing with. However, we tend to do our research in original languages. This is very important for us to stress, because sometimes there can be a misunderstanding that Slavs and Tatars is some sort of cultural tourism – that we are going to certain areas of the world, reading things, coming back and presenting them. And that is not accurate, since we do research in Farsi, in Russian, in Polish… so as we come to Eastern Germans – we don’t speak German. So we don’t feel particularly qualified to address the issue.

Kha-Kha-Kha, 2012, Projects 98, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Kha-Kha-Kha, 2012, Projects 98, Museum of Modern Art, New York

For us language is absolutely fundamental. Speaking different languages provide a sense of “productive schizophrenia”. As you know, when you speak another language, you are a different person. First of all, your sense of humour is different. And this multiplicity of personalities is important. Somebody earlier asked us about how do we deal with the idea of nationalism. And our response has been from our experience: the only way to deal with this issue was to collapse it by overburdening it. It doesn’t mean Slavs and Tatars have no national identity. To the contrary – we are Eurasians and therefore we have many identities – not just Polish, not just Russian, but Polish, and Iranian, and Russian, and so on, and what’s interesting is the negotiation between these sometimes conflictual identities.

Okay, but now this sounds highly postmodern. Whereas in your publications you strongly emphasise the specificity of your approach against both modernism and postmodernism, by calling it antimodern. What exactly do you mean by that?

The antimodern is a very important position for us – of our relationship to time, history and the idea of progress. We are interested in moving forward, but we want to do so looking backward. For us it is an urgent response to contemporary society – which is too often amnesiac. This sense of time is very much Slavic – for example in Russia, what happened 400 years ago is spoken in the same way as what happened four years ago. So there’s a sense that current real estate prices in Moscow are just as much the fault of Ivan the Terrible, as Putin (laughs).

KhGiveth, 2012, Projects 98,

KhGiveth, 2012, Projects 98,

Museum of Modern Art, New YorkWhat makes it different from postmodern?

Postmodernism tends to be, in our opinion, somewhat hysterical. The antimodern takes polemical positions vis-à-vis the past and the thorny issue of traditionalism. The likes of Virilio and Baudrilliard would never acknowledge that there are such things as universal values. We have no qualms in embracing this notion, no matter the difficulty or challenges. People might consider this conservative, but honestly we don’t know why, since we consider it today just common-sense if not radical. The antimodern can say: “Certain things have existed for thousand of years – and that’s okay.” In today’s amnesiac society, that offers a certain rupture.

In Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz you explore parallels between Polish and Iranian culture. Apart from the baroque sarmatism, you’ve also linked the Iranian Revolution, the triumph of Polish Solidarity movement and the recent collapse of the financial market. What brings these facts together?

1989 and 1979 stand as opposite bookends. If 1989 was the end of one narrative which determined the course of the 20th century, communism, then 1979 was the beginning of another narrative – that of political Islam – which is considered the major geopolitical challenge of the current century. Why 2009 then? When we began this research, the world began to come to terms with another crisis, the financial crisis, which is the failure of another model, that of liberal capitalism. Only three months after we started doing the research, the Iranian presidential election occurred and the protest that followed opened another chapter in this unlikely relationship between two countries, Poland and Iran, and their quest for self-determination. The Green Movement in Iran looked to Poland as the most successful example of civil disobedience and for the first time, writers and thinkers like Kołakowski, Bauman and Miłosz were translated into Persian.

Political Islam is in a way a hot topic nowadays – there is a lot published about it. What makes your approach different than any other?

Molla-the-AntimodernOur practice resembles the offer and scope of a middle-eastern bazaar, in a maximalist sense there’s something for everybody. So when we approach a subject that is complex – let’s say the relationship between Poland and Iran – this is a story you cannot tell simply through one sculpture. But you can begin to do justice to its complexity through a sculpture, an installation, some textile work, a publication, lecture and a balloon. So a person who is more literary minded might like to read a book while someone else might prefer something more performative like a lecture. A child most likely opts for the balloon. There is a kind of fanning out of media.

Molla-the-AntimodernOur practice resembles the offer and scope of a middle-eastern bazaar, in a maximalist sense there’s something for everybody. So when we approach a subject that is complex – let’s say the relationship between Poland and Iran – this is a story you cannot tell simply through one sculpture. But you can begin to do justice to its complexity through a sculpture, an installation, some textile work, a publication, lecture and a balloon. So a person who is more literary minded might like to read a book while someone else might prefer something more performative like a lecture. A child most likely opts for the balloon. There is a kind of fanning out of media.

Another distinction is this idea of substitution – reading one thing through another. It’s counterintuitive in a way. We say: “Okay, if you want to understand political Islam, perhaps it’s best we look at the history of communism; if you want to understand the contemporary Iran – let’s take a look at Poland and Solidarność.” There are lots of books about Iran and the US, about the US and Poland, Poland and Russia etc. But we’re interested to look at Iran through Russia or Poland: and that is the crux of our new cycle of work, The Faculty of Substitution.

There seems to be a tension in undertaking the topic of Islam and linking it with communism. It sounds explosive as a combination.

It is funny you say that, since for us it’s a way to diffuse the tension – to make Islam less scary by comparing it with communism. Of course for some people these are two of the biggest threats to Western liberalism. But for us bringing them together helps demystify the controversy, the noise. Nobody links Iran and Russia together, which is quite surprising since they have been historical enemies for some 400 years. Many of the former Muslim-republics of the USSR and before that the Russian Empire were previously part of the Persian Empire – from Armenia to Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan to Tajikistan.

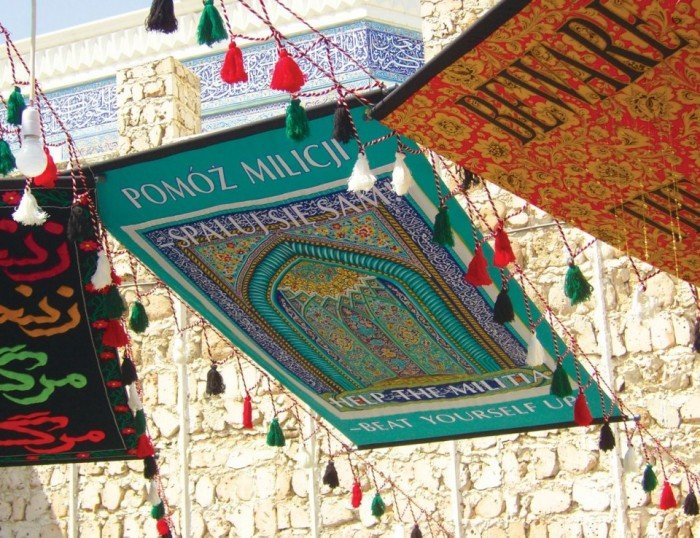

Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, Saharjah Biennale, 2011

Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, Saharjah Biennale, 2011

Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, about Iran and Poland, was first presented at the 10th Sharjah Biennial, in the Emirates. This was a turning point in our practice. On the wall of this old heritage house we have “Long live long live, death to death to”. This is a celebration of life. Instead of celebrating a country: “Long live Iran” or “Long live Poland” or “Death to America”, we celebrate the idea of celebration, condemn the idea itself of condemnation. Long live to the idea of long live and death to the idea of death too.

Once inside, people could sit underneath an array of banners with different, often hybridised, themes from the Iranian Revolution and Solidarność and have a cup of tea, read the 79.89.09 newspaper. What’s important to note: we had local people – not just art pilgrims – but those Afghans who baked bread around the corner, Emirati couples escaping for a moment of rest, men going to the Shi’ite mosque next door, construction workers coming to sit down and take a nap. It was very important for us, that it did not look like art – it was not intimidating, it was not cold, it was not preaching or pretentious. It did not say: “You should learn about this,” but rather: “Come, if you just want to have a cup of tea and a break – great. You don’t have to engage further if you don’t wish to do so. If you look and think about them – even better. Same if you want to read – the more you invest, the more you’ll get out.”

Do you think perhaps your relative success might be caused at least to some extent by Western people’s fear of Islam? Maybe that’s the reason your art has become compelling, because it responds to these fears or even provides some kind of remedy – enables to tame it, by evoking the fear while keeping it at a safe distance.

Our work is not for only western European and American audiences but also for people in our own region – it presents our own histories in a way which privileges complexity, re-activates traditions and histories often considered irrelevant or arcane. It is very important for us to have feedback from Serbs and Slovaks, Armenians and Azeris: since we must first understand the value of our own history before expecting others to take any notice or interest. Too often the region is perceived as homogeneous, destructive, violent or simply “problematic”.

In Vienna with your Not Moscow Not Mecca exhibition you had also to cope with identity of the place – the Secession Pavilion is a hallmark of modern art: it inherits perhaps an Austro-Hungarian spirit of syncretism, wealth, decorativeness and deep symbolism, that were significant for art nouveau.

At the Secession, we decided to tell the story of syncretism through the perspective of fruits, via a shrine of fruits of different media. Outside the Pavilion greeting visitors were watermelons, a simple fruit through which we could tell certain complex stories. A watermelon is in some sense the fruit of the Other. For example in America watermelons are used as a racist shorthand for African-Americans. In Europe they are imported from the very countries with which Europe has tense immigration issues – North Africa, the Middle East, Turkey. In Russia, watermelons come from the Caucasus, another area of conflict within the Russian imagination. So the fruit exemplifies a kind of cognitive split –refreshing, announcing the arrival of summer, of warmer climes, it’s a consensual fruit, and yet it brings to mind another, more conflictual relationship.

Not Moscow Not Mecca, Vienna, 2012, photo: courtesy of Secession / Oliver Ottenschläger

Not Moscow Not Mecca, Vienna, 2012, photo: courtesy of Secession / Oliver Ottenschläger

For last 6 years you publish, exhibit and lecture in art institutions all around the world. In Warsaw you gave a talk about one of your recent projects – Molla Nasreddin. To my ears this was a typical lecture about modern visual culture, that could have been given by a scholar at a university. It wasn’t a performance at all – rather a typical paper, wouldn’t you agree?

We take that as a compliment, thank you. We admire work of academics and we often turn to their work for research. Within the art context, people often call our lectures “lecture-performances”. And, in all humility, we don’t believe there’s anything performative in it. I think the reason why people call it a “performance” is very stupid – it’s because…

…it happens in art institutions?

Yes, for starters. And because people who normally give lectures – whether in the academy or art – are not the best speakers so when a talk is delivered well, what we consider a minimum requirement, a given – it’s considered a performance.

You put great emphasis on the role of printed media and verbal communication, which could be construed as going against the grain. You absorb your public with books and papers – something that requires time and focus. Whereas a wall text in art museum is supposed to be no longer than a text message, Slavs and Tatars offer intimate spaces and personal contact as a kind of alternative to this remote-ness. How will you survive in era of new media and augmented reality?

We would like to push the model even further. If during the first two or three years of our practice we focused exclusively on print, on publications, in the past two or three years we’ve worked with many other media: from performances to installation, sculpture, to textile work. But the book remains the crux of the work: we’ve maintained our focus on publishing, this year alone will see three new books. In fact, contrary to popular practice, all the other media are a premise, an agent to bring people back to the book. In art, the book is often just an afterthought – it catalogues the exhibition, serves as documentation, essentially a marketing tool. But for us, the book is a platform for further knowledge and research. It is – like you said – the core.

So tell me – do you find yourself more as curators, artists or academics?

We appreciate the work of curators and academics; in the end, we’re just thinkers thinking through art.

My point is, we do not need necessarily to focus on the notions we already have in language. In fact by your work you seem to extend and modify the present idea of being an artist or the idea of being a curator and critic, by bringing it closer towards university, journalism or even social entrepreneurship. I also think you became recognised by the art world, since there is already a need for what you are doing. Only there is no name for it yet. And hence your popularity.

Whether these notions are changing or not is actually a good question, but it’s not clear whether society at this stage needs to burdened with a breakdown of categories. People want to have clear ideas, distinct categories – they want to recognise: this person is an artist, this one is curator, the other is an art critic and that one is a collector. We don’t believe in re-inventing the wheel: otherwise it is easy to focus on the context instead of the work itself. We present the work within pre-determined categories and ideally subvert these distinctions from within, subtly, quietly, joyfully.

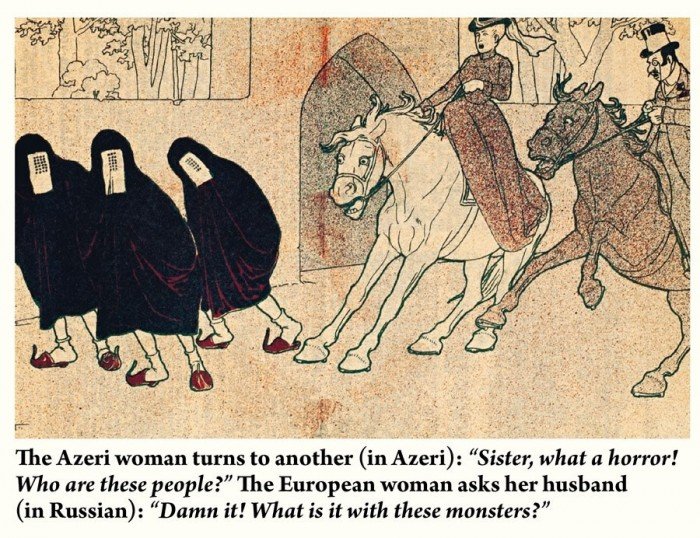

One of the satirical pictures from Molla Nasreddin publication by Slavs and Tatars.

One of the satirical pictures from Molla Nasreddin publication by Slavs and Tatars.

Okay, now let me ask you one more question… I left it at the end, since this is something, you might be bothered with: you explore idioms that seem extremely arcane and exotic to Western public. At the same time you interpret them within a framework of Western intellectuals – Bataille, Benjamin, Foucault – and represent these idioms as if they were elements of Western mass-culture. My question is: how do you avoid a risk of colonialisation of Eurasian identity? For example Molla Nasreddin is something interesting for the public, because of being strange, exotic, new, weird – and such attitude seems hardly transformative.

Our work is as influenced by figures from the East – be it Shariati, Suhrwawardi or Molla Nasreddin – as those you mention. It is our challenge to make these things not far, but actually very close. In fact Molla Nasreddin is not very different from the satire you can find in Poland or Russia or in the United States. The question of exoticising a given subject assumes there’s a fixed East and fixed West, that there is an “us” and there are “others”. Our work is I hope transnational, it belongs to many traditions at once. We try to find what is common amongst these cultures, both bottom up and top down. In fact we act like mediators or even post-national-mediators. We don’t belong to a single nation – we are intellectually and affectionately as Russian, as we are Polish, Iranian or American…