ALAN LOCKWOOD: As chief curator of drawings at MoMA in New York City, you began the museum’s collection of Alina Szapocznikow’s work and proposed that MoMA collaborate in the solo exhibition of her work, Sculpture Undone, which has opened 7 October 2012. How are audiences in U.S. responding to this artist who was all but unknown there a few years ago?

CORNELIA BUTLER: At the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, Sculpture Undone was a show that artists responded to very well. The broader audience didn’t – there was one mixed review, so it was a bit of a sleeper. In New York, there’s a lot of excitement. A lot is from artists, again. That – along with the work’s influence on a new generation of artists, like Paulina Ołowska – is always the biggest vote of confidence, the thing that says to me that the timing is right. There’s a review in the New York Times today that’s quite a nice review (11 October 2012 – A.L.). It’s a very focused show, it’s not huge and I think that’s good – often a focused, mid-sized retrospective is just right for the audience. It gives them a good immersive introduction but it’s not exhausting.

Cornelia Butler

Cornelia “Connie” Butler has been The Robert Lehman Foundation Chief Curator of Drawings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York since 2006, and co-organised the exhibition Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone and contributed an essay to MoMA's exhibition catalogue. Ms. Butler’s other recent MoMA exhibitions include the surveys Greater New York and On Line, which covered 20th century drawing, and she is co-organising the first North American retrospective of the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark’s work, opening at MoMA in 2013.

MoMA, NYC

Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972

7 October 7 2012 – 28 January 2013

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Alina Szapocznikow: Du dessin à la sculpture

27 February 2013 – 20 May 2013

When did you begin exploring Szapocznikow’s work?

When I was in Los Angeles working as a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, around 2003. Monika Fabijańska from the Polish Cultural Institute was doing a lot of work there, and we met as I was working on this project on feminist art.

This was the project that become your exhibition WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, which travelled to the National Museum of Women in Washington, D.C., and to MoMA in 2008?

Yes. Monika invited me to come to Poland in 2004, with curators who were particularly interested in women artists, including Maura Reilly, who was working on Global Feminisms for the Brooklyn Museum. Monika was very keen on my seeing Szapocznikow’s work, in addition to artists such as Ołowska. It was a fantastic trip, visiting the generation of artists of the early 2000s while looking at this historical material. Others had begun suggesting Szapocznikow to me. But I remember looking at the Zachęta catalogue by Anda Rottenberg and having this visceral, bodily reaction to the work, but not responding to it mentally. I just didn’t get it.

Cornelia Butler, photo: courtesy of The Museum

Cornelia Butler, photo: courtesy of The Museum

of Modern ArtYou say it was a visceral response, but also that you didn’t get the work?

My first introduction to it was Herbarium, the last work, the body imprints. I read it through this essential feminist perspective, and felt that it was too literal, too romantic. I think now that I didn’t really understand it. Then I saw more of the work in Polish collections, the mid-1960s Pop Realism, the lips and the breasts and figures. I still didn’t have a full picture of what the work was, and decided that Szapocznikow, like Lee Bontecou and other artists I’d thought about for WACK!, that they were proto-feminists, and didn’t make sense for the show. I now think that may not have been the right decision.

WACK! covered the years between 1965 and 1980, and included the Polish artists Ewa Partum and Magdalena Abakanowicz.

Poland was quite present in that show. I understood that a number of women there were working in a feminist idiom, like Natalia LL. It was really useful to see how they were dealing with gender, largely coming out of the field of conceptual art. Then when I moved to MoMA several years later, I was invited to the conference in Warsaw.

This was the Szapocznikow conference “Documents, Works, Interpretations” in 2009, held during the Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art’s “Awkward Objects” exhibition.

Yes. I gave a talk that was really an attempt to insert Szapocznikow back into “WACK!” after the fact. And about how I might have made a context for her. The experience of being in that conference, immersed in Szapocznikow for two days, left me astounded by the breadth of the work, and its ability to absorb many different readings and to withstand many different meanings. You don’t often find a body of work that’s twenty years long that can sustain the range of really sophisticated interpretation that was brought to bear on it. From looking at the war, the camps and how that figured in to the work or trauma, and then at any number of subjects. That’s what did it for me. I began wanting to do something, and realised that there was a context for the work outside of Poland, too.

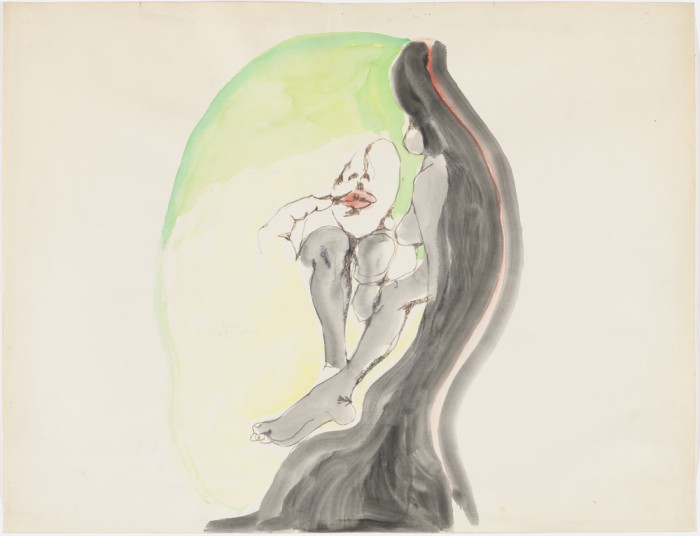

Alina Szapocznikow, Petit Dessert I (Small Dessert I),

Alina Szapocznikow, Petit Dessert I (Small Dessert I),

1970–71. Kravis Collection.

© The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanisławski/ADAGP,

Paris. Photo: Thomas Mueller, courtesy Broadway 1602,

New York, and Galerie Gisela Capitain GmbH, Cologne.What did you say in your conference presentation, “Soft Bodies, Soft Sculpture”?

I tried to set Szapocznikow’s work against, or with, that of some of her international counterparts, Louise Bourgeois, Hannah Wilke, Eva Hesse. At the time – and I don’t think this was necessarily right but I was trying it out – I was thinking about the idea coming from Louise Bourgeoise of the femme maison, the house as the body, the architecture of the body, the body as an architectonic form. I had been thinking about Szapocznikow’s move from representing vertical figures to horizontal ones, which is a move that Bourgeois makes, and her moving from the exteriority of the body to a kind of interior or anatomical embodiment. And then about setting her up against figures including Niki de Saint Phalle, who she knew in Paris.

What were you hearing during the conference that provided your sense of the work’s ability to absorb or resist different meanings?

I hadn’t known before the Warsaw conference that there was younger generation of scholars who were all deeply committed to the work. Manuela Ammer was doing work on Szapocznikow’s conceptual art, the Photosculptures series and the conceptual proposals. Paweł Leszkowicz came from the queer perspective, reading the late sculpture “Piotr”, of Alina’s son, in a particular way. Griselda Pollock talked about trauma, and Agata Jakubowska had done extensive work on feminism in Poland. For me, it was a huge learning curve. I started thinking about what could make sense at MoMA or in the context of the United States. And realised there are many ways of accessing the work that would make sense for the American audience.

Did you know at that time that MoMA would become involved in the “Sculpture Undone” project?

No. I returned with the idea that I would propose an exhibition at the museum. Then heard that Elena Filipovic was working with Joanna Mytkowska, and I also spoke to my colleagues at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Instead of proposing my own project at MoMA, we invented this collaboration with Elena and others, then I proposed to the museum that we get on board with the project that became “Sculpture Undone”. What’s interesting is that there was critical mass of us in different parts of the world who all wanted to do something.

Exhibition view, courtesy of MoMA

Exhibition view, courtesy of MoMA

How did Anke Kempkis’ show, back in 2007 at her New York gallery Broadway 1602, fit in to the Szapocznikow timeline for you and for MoMA?

Anke’s show was an important earlier part of the timeline. We had already bought some work from that show before I made the proposal at MoMA. Anke’s depth of knowledge had been very important for me after I first travelled to Poland, as was the chance to see the response to the work here, including an enthusiastic review in the New York Times (28 December 2007 – A.L.). Anke made very good selections from across the career – she’s a gallerist who thinks like a curator and does deep scholarly work. MoMA purchased drawings as the result of her show, and sculpture as well – or people close to the museum purchased sculpture, and then made it a promised gift to the museum.

What were the drawings?

I made a selection thinking of what would represent Szapocznikow well, if that was the last work available – one did not know at the time what else might be in her son Piotr’s archives. We purchased an early drawing related to one of the monument proposals, and a late Human Landscape, one of the drawings with colour in it, really fantastic and rather a large sheet. And there were two monoprints and other works. One collector who funded a number of these purchases was Harvey Shipley Miller, who had built the Rothschild Collection of drawings at MoMA. Not knowing anything about Szapocznikow, he walked in to Anke’s show and just fell in love with the work.

That was the beginning of MoMA’s Szapocznikow collection. How does the current exhibition work for the museum’s mission, and how do you find the installation looks in the museum galleries?

Part of the excitement about it, frankly, is that the work has been at enough art fairs that collectors have seen bits and pieces of it and are very excited to see more in the breadth that the museum’s show provides. During the opening week, people were saying how great it was to see the body of work, or a range from it. I think that at MoMA, with our collection of postwar art, and works of New Realism and postwar abstraction, there’s a context for it there, for collectors and the wider audience. I also love the space that it’s in, in the older part of the building. It has beautiful, large, curved windows on one side, on 53rd Street. Then on the other side, her sculptures overlook the sculpture garden. In the MoMA installation those are her early, figurative works, and down in the sculpture garden you have Cezanne and Matisse and David Smith. We wanted to make that connection, and I think it is lovely.