September 9 and 10, at Wrocław’s Centennial Hall, two stars of alternative rock (Jonny Greenwood) and electronic music (Aphex Twin) will perform pieces inspired by the star of contemporary classical music: Krzysztof Penderecki. Held as part of the European Culture Congress, the concerts will feature three pieces composed in the early 1960s, when Penderecki’s name was synonymous with strong, avant-garde sonorism.

Krzysztof Penderecki

Krzysztof Penderecki

photo: ECC promotional materials“I started experimenting, for instance with the double bass. […] You couldn’t just make these sounds up”, recalls Krzysztof Penderecki. Nevertheless, the sounds came as a shock to contemporary audiences and musicians alike. It was believed that the young composer, for reasons unknown to others, was using instruments “in ways they were not intended to be used”, as Zygmunt Mycielski put it.

These claims now come across as amusing: isn’t producing sounds the intended use of musical instruments? It would have been more precise to say: “contrary to their typical use”, which was the actual cause of the indignation. Penderecki’s earlier work, with his 1960 Threnody being the prime example_, continues to embody chaos and mindless shocking to those who expect the violin and cello to produce no more than a “beautiful song” that soothes the senses without interrupting one’s sleep.

Penderecki, Aphex Twin, and Greenwood at the ECC in Wrocław

Aphex Twin is one of most celebrated names in contemporary electronic music; the first techno artist whose work was arranged for orchestra and performed at concert halls across the world (including the London Sinfonietta and Alarm Will Sound).

Jonny Greenwood, the lead guitarist of Radiohead, is a composer who feels completely at home in the “classical” instrumentarium and who has expressed his fondness for Krzysztof Penderecki’s music.

The European Culture Congress in Wrocław will host two concerts (Hala Stulecia, September 9–10, 7:30 PM) featuring performances of three pieces by Krzysztof Penderecki: Polymorphia, Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, and Kanon. Aphex Twin will perform a piece of his own composition titled Polymorphia Reloaded, while Jonny Greenwood will present 48 Responses to Polymorphia. Both pieces will have their world premiere performances in Wrocław.

The same Zygmunt Mycielski described Threnody as a piece that “ought to be bad, yet is good. Like oysters, escargot, and vodka”. It is a precisely-constructed piece, built upon canons of 36 to 52 voices and conveying sounds that burst with expression. Penderecki opens this study of the expressive capabilities of stringed instruments with a “poignant ‘scream’ of the highest possible sounds”, as Mieczysław Tomaszewski wrote. Then a seeming chaos of sounds erupts, produced by those “weird” techniques: sounds that are dry and wooden, rough, metallic and slippery, sharp, and shrill, as well as expanding and massive sounds, with internally diverse groups of instruments and shifting dynamics; in juxtaposing ranges and single, spatially and temporally scattered explosions. Yes, to explore these pieces is to wander through a minefield in a thickening and increasingly hostile atmosphere.

It is difficult to separate the perception of this atmosphere from the meaning of the title. Although Penderecki himself initially titled the piece 8’37”, in the technological manner of the most abstract avant-garde music, Jan Krenz sparked a discussion about the expression of the piece during rehearsals. This lead to a new choice of title, Threnody, which the publisher, PWM director Taduesz Olszewski, appended with a dedication “for the Victims of Hiroshima” (supposedly without the composer’s knowledge).

“‘Sound for sound’s sake’ has never interested me”, claimed Penderecki years later. Threnody appears to prove this assertion. The music is “pure”, yet highly expressive, and — in the common intuition of its numerous performers and listeners — deeply dramatic. Although the piece has appeared in a variety of contexts, even in such pop-cultural ones as film soundtracks, and despite it’s declarative title, it escapes trivialization. This is an attribute of a masterpiece.

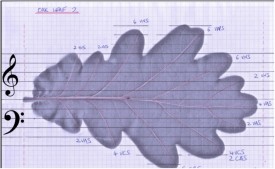

Part of the score by Jonny GreenwoodThe same listeners who ridiculed the unwillingness of musicians to destroy their instruments by performing Threnody soon lambasted Penderecki for the coda of his next piece for strings, Polymorphia (1961). As the title announces, the composer explores — even more boldly than in Threnody — the multifaceted sounds of an ostensibly homogeneous string orchestra. The piece is more than just ranges, clusters, and percussive effects: it is a wavy, semi-liquid texture, an even more colorful variety of music that teems with activity and surprises us with “ugly” sounds (is there any point in using that term anymore?) that add drama. And, finally, that incriminating C major triad, that spectacular “betrayal of the avant-garde”.

Part of the score by Jonny GreenwoodThe same listeners who ridiculed the unwillingness of musicians to destroy their instruments by performing Threnody soon lambasted Penderecki for the coda of his next piece for strings, Polymorphia (1961). As the title announces, the composer explores — even more boldly than in Threnody — the multifaceted sounds of an ostensibly homogeneous string orchestra. The piece is more than just ranges, clusters, and percussive effects: it is a wavy, semi-liquid texture, an even more colorful variety of music that teems with activity and surprises us with “ugly” sounds (is there any point in using that term anymore?) that add drama. And, finally, that incriminating C major triad, that spectacular “betrayal of the avant-garde”.

Penderecki according to Markowski

Polskie Nagrania recently released a unique record titled Awangarda, containing Krzysztof Penderecki’s most outstanding work from the late 50s and early 60s (Psalms of David, Strophen, Anaklasis, Dimensions of Time and Silence, Threnody, Fluorescences, and Polymorphia) in the worthy interpretations of Andrzej Markowski.

But in Polymorphia, the sporadic euphonic harmony foreshadows that finale, emphasizing the contrast and building expression deep into the piece, which is evidently a narrative and dynamic work. Yet the C major chord rings somewhat ironically. Only the unfailing Bohdan Pociej managed to find in it the “majestic loftiness” present in Penderecki’s other work. I admit that I hear the fully exploited expression of sound and the material itself. Perhaps this is the reason why this emphatic music is so eagerly used by filmmakers (e.g. Kubrick’s The Shining). The piece will now be attempted by Greenwood and Richard D. James, two artist who hail from the ultra-expressive realms of rock and cold, contructivist electronic music. Polymorphia combines equally disparate aesthetic stances.

Of the three Penderecki pieces selected for the retrospective in Wrocław, Kanon (1962) provoked the greatest yet briefest controversy. During a concert at the 1962 Warsaw Autumn Festival, a group of young audience members booed the piece, after which it was performed less often than the composer’s other work. It is neither as expressive as Threnody or Polymorphia in its premise, nor as diverse in terms of sound. It it largely a contrapuntal and constructive exercise: in the culminating point of the piece, the composer intertwines 208 voices, a measure that nevertheless remains unnoticeable to the listener. But the work also poses technological challenges that were not trivial half a century ago: during the performance, the orchestral theme, along with its polyphonic variants, is recorded on tape and played back, after which the live orchestra joins the recording in a counterpoint. Mycielski was among those whose reception of Kanon was critical, writing that “it sounded as if the score had been written by a composer striving to achieve a musical effect solely through gesture: increasing mass, scattering, fading, and accent, but without the use of notes.” Can these words still be regarded as accusations?

The musical form of Kanon contains surprising premonitions of the noise aesthetic (who cares if the premise is completely different) and the contemporary electronic experiments conducted by Aphex Twin. Listening to this somewhat forgotten piece brings back memories of the 2009 performance by Aphex Twin and Florian Hecker at the Sacrum Profanum festival in Kraków. Looking down from the ivory towers of “high art”, one might get the impression that Penderecki’s sacred is in fact blending with the pop(-sub-)cultural profane. But what has become of the border?

Sources:

K. Penderecki, Rozmowy lusławickie, vol. 1, interviewed by M. Tomaszewski, Olszanica 2005;

M. Tomaszewski, Penderecki. Bunt i wyzwolenie, vol. 1, Kraków 2008;

K. Penderecki, Labirynt czasu. Pięć wykładów na koniec wieku, Warsaw 1997.

translated by Arthur Barys