I left the New Horizons festival and headed straight for the Two Riversides festival. I knew that a lot was going to change, even before I arrived at my destination. On the one hand, there was Wrocław, with its hotels, trams, construction work, salad bars, pubs, ethnic supermarkets, and multiplex cinemas; a program that drives you to despair: movies from morning until night, screened in over a dozen theatres with AC; roomy, comfortable chairs with cup-holders. And on the other, there’s Kazimierz Dolny, with its small square, the hub of all the events, a handful of bars, just two movie theatres, the larger of which is set up under a tent: you sit on plastic chairs with wooden planks under your feet, grass sprouting out from the cracks; some people show up with their dogs. The programme doesn’t offer much choice; there are no heavy-hearted decisions to be made.

5. Two Riversides festival,

5. Two Riversides festival,

30 July – 7 August, 2011On one of my very first days in Wrocław, I ran into an odd man with two hats on his head, a bulging shopping bag in his hand, and two plates in front of him. Being the pushy type, he of course invited himself over to my table. After a moment, he asked me riddle: “How much is 2÷2×2?” Some people would say 2, others answered ½. Why the discrepancy? The answer was simple: there are different schools, different cultural codes. The former answer was correct in America, the latter in Poland. The mad mathematician/hatter based an entire theory about the state of the Polish and American economies on this difference. The US economy was better off because its math always produced a higher sum. The current financial crisis in the US, the one incessantly discussed on TV, seems to contradict this theory/speculation, but I digress.

I also ran into someone in Kazimierz Dolny, someone completely different. I’m wary about building complex analogies around these encounters, so please ad lib whatever I hesitate to write explicitly. Anyway, I met a Gypsy fortune-teller in the small town on the Vistula. She said nothing about numbers, but she did manage to slip a few coins out of my pocket. It all started with her praising my beard and claiming that I belonged to a social group known as “the dark ones”, which I was more than happy to confirm. Having finished with the pleasantries, she pulled out her cards and grabbed my hands. She said I had a happy future ahead of me, with a blonde and car that I have no intention of buying. And she also said I would end up rich.

Later in the day, I caught a glimpse of the Gypsy woman speeding home in a Mercedes with her girlfriends. They were being driven by a chauffeur (!), one whom I had never seen before. I went back to the film screenings.

At the Two Riversides festival, movies often take second stage to meetings with the people behind the films. There’s nothing wrong with that, especially since these events are held in a lively, unpretentious atmosphere. Audiences eagerly participate in the dialogue; there’s no ironic smirking. They ask questions, request autographs, and line up for group photos. With all its mingling with the stars, isn’t the festival as pretentious as the one in Międzyzdroje? As it turns out: no. No one forgets themselves in Kazimierz. The atmosphere is provincial: director appearances are accompanied by the buzz of espresso machines, people lining up for pastries, and slamming Porta Potty doors. There are no red carpets: the space set aside for Q&A’s is carpeted with strips of artificial grass.

***

This year, Grażyna Torbicka and her team opted for variety: none of the retrospectives were exhaustive, but there were quite a few of them. Liliana Cavani, Grzegorz Królikiewicz, Leonardo Sciascia, Andrzej Kondratiuk, Roberto Rossellini — numerous classics. Among the young filmmakers featured at this year’s festival, Pablo Larraín turned out to be a true revelation. With just three films under his belt, it is apparent that this Chilean director has a promising future ahead of him.

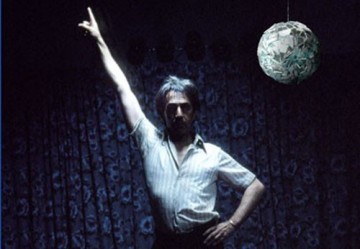

Larraín obsessively revisits the Pinochet era. His best-known film, Tony Manero, which won awards in Rotterdam and Warsaw, tells the story of a certain Raúl Peralta, a criminal, lowlife, and choreographer obsessed with the main character of Saturday Night Fever. Hence the title of the film. An insane man: impotent, a murderer, a two-bit artist, one just as crazy as the times he lives in. Santiago de Chile under Pinochet is depicted as an Apocalyptic wasteland. The streets are combed by military trucks and the unmarked cars of the secret police. People walk on walls, slinking by with heads down, and lock themselves up in the decrepit ruins of houses that offer little shelter from the outside world. Raúl, aka Tony Manero, is a child of his times: a terrifying monstrosity clad in a tacky snow-white suite, a black open-necked shirt, and shiny patent leather shoes. It’s an intense film that takes the cliché of the serial killer and plants it in the powerful imagery of a totalitarian world where even dreams become sick. Definitely one of the top films of the festival.

Tony Manero, dir. Pablo Larraīn

Tony Manero, dir. Pablo Larraīn

Two other films explored convention in interesting ways: Small Town Murder Songs by Ed Gass-Donnelly, and Meek’s Cutoff, directed by Kelly Reichardt. The first is a play on the dark crime film genre, while the other references the Western. The events take place in small Ontario Mennonite town where nothing much ever happens. One day, a body is found: the massacred corpse of a young girl. Walter, the middle-aged, mustachioed local policeman tasked with the investigation, appears honest enough in the beginning. But the skeletons in the cop’s closet come back to haunt him: the dark ego of law enforcement that he tries to forget and suppress. The success of the investigation hinges on his failure to repress his past. A bitter, Pyrrhic victory awaits Walter. The fatalism of the story is driven home by the direful music of Bruce Peninsula: the deep sounds and steady drumming forebode the inevitable.

The downward spiral marks ever-widening circles in the lives of the characters in Meek’s Cutoff as well. The year is 1845. America is still a wild, sparsely-populated place. Desert as far as the eye can see. The camera is almost always focused on three couples and their three wagons. Led by a quaint tramp, they wander across a wasteland in hopes of reaching the promised land. Their route was supposed to have been a shortcut, but the road winds on with no end in sight. The settlers begin running out of food and water, and to make matters worse, an Indian appears out of nowhere. Reichardt juxtaposes the heroism of the early Americans with the ruthlessness of nature. But she makes no attempt to deconstruct the myth of the Wild West. The film isn’t even an anti-Western. It isn’t motivated by a need to dispute anything or to fight any conventions or stereotypes. The events are set in an endless sea of nothing, through which a few people roam aimlessly. There’s nothing to gather, nothing to sow, no one to ridicule, no one to kick.

Meek’s Cutoff, dir. Kelly Reichardt

Meek’s Cutoff, dir. Kelly Reichardt

***

Contemporary cinema thrives on hopelessness. Kazimierz, like New Horizons, is an incessant act of communion: the artists place razor blades on the viewers’ tongues. It brings to mind that unforgettable scene from the TV show Carnivale. Depression, angst, dejection, misery, and general unhappiness. How much can you take? Cioran, for instance, reveled in darkness, but is said to have loved chocolate. There are pictures showing him devouring the treat with a grin on his face. It’s that fissure I seek more and more as I become exhausted by festival films. I didn’t find it in Kitano’s Outrage. The Japanese director tells yet another story about the Yakuza, people who willingly cut themselves off from the world and shut themselves in greenhouses, where they wait until the tables have turned and the hunter becomes the hunted. There are two directions in this world: demotion or promotion, which sooner or later ends with a fall and death. It’s sad watching these pawns who don’t even realize what they’ve gotten themselves into. One might attempt to build a metaphor for fatalism on this flimsy cliché, but there’s probably no point.

Lynne Ramsay, author of the film We Need to Talk About Kevin, was another disappointment. I wouldn’t even criticize the film’s gloomy outlook; how else do you make a film — entirely indigo-toned — about a mother whose son decides to murder as many of his schoolmates as he can? But I do resent that she quickly veers away from an unpopular subject, changing a story about how motherhood need not always be a heavenly gift into a tale about a clever demon, an heir of Satan who sows destruction for the same reason that the Joker does: just because.

We Need to Talk About Kevin, dir. Lenne Ramsey

We Need to Talk About Kevin, dir. Lenne Ramsey

In contrast to most of the movies, the film by the Dardenne brothers, which opened the Two Riversides festival, actually seeks other colors. And yet The Kid with a Bike is the weakest film in the duo’s career. The Belgian filmmakers tell yet another story about a child. And once again, it is a lost, lonely, hyperactive child. We constantly see him in motion: sprinting around, running errands, setting his grand schemes in motion. Who knows where the mother is. His father isn’t too eager to spend time with him either, fearing that the boy will disrupt his plans, but he can’t bring himself to tell him. The film is great up until that point, but then everything suddenly goes downhill, like in We Need to Talk About Kevin. A teenage gangster and a good-hearted hairdresser enter the picture. Psychomachia, a struggle for the child’s soul, begins: a simplistic, naïve, and obvious fight. The film is just a few steps away from a Sunday night made-for-TV movie. It is only thanks to the fantastic actors that The Kid with a Bike avoids docking in that port: it is they who win the struggle against the banal drivel written for them.

Interestingly, The Kid with a Bike tied for the Grand Prix at Cannes with Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, which closed this year’s festival in Kazimierz, and was undoubtedly the festival’s best picture, a whole class above the piece by the Dardenne brothers.

Ceylan doesn’t try to stay in place; his films constantly evolve. In his latest movie, the maker of Uzak experiments with the police film genre. For over two hours, we observe an investigative team comb a crime scene with two suspects, a doctor, military officers, and prosecutors. Nothing goes as planned. Night falls and the temperature drops. Their irritation grows with every passing hour. They turn to talking to calm their nerves. They talk about everything: their wives, mistakes from the past, work techniques, and doubts. The director gives them a chance to speak their minds, but he isn’t above occasion absentmindedness. In one excellent scene, the camera follows an apple as it rolls downhill. We hear stories being told in the background, but the only image we see is the fruit that hung on a tree just a moment earlier.

The night draws to an end. Everyone is exhausted. The doctor, who becomes the main character at one point, has an autopsy left to conduct in the morning. After he finishes, he presses his forehead up against the glass. Through the window, he sees the dead man’s wife and son, brought in to identify the body. The walk up a country path, over a gentle hill, and find a soccer field. The ball rolls up to the boy, who kicks it back to the players out of habit. No, this gesture doesn’t mean that the ball is his salvation and that people are capable of forgetting about anything. The kicking of the ball is just a signal, the image I have been looking for, a return to life: sad Cioran’s chocolate.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, reż. Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, reż. Nuri Bilge Ceylan

translated by Arthur Barys