Biweekly: How did it happen that you have started to work with theatre?

Julia Rowntree: I did a French degree and arts degree at University and eventually I got a job in an animation company. I made animated films for ten years as a producer. We made feature films and commercials for television, so for the commercials, I was used to making a translation between artists and the needs of the commercial world. I knew Rose and Lucy [Rose de Wend Fenton, Lucy Neal – ed.] who set up London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT). I’d known Lucy since she was fourteen and I was a little bit older. I loved what they were doing. When I went on holiday they used to do my job. They told me that’s where they learned how to do invoicing etc. I used to give them some advice.

Julia Rowntree

Senior arts development professional, former Director of Development, London International Festival of Theatre, and author of Changing The Performance - A Companion Guide to Arts, Business and Civic Engagement, published by Routledge. Currently co-directing a participatory ceramics project in the lead-up to the London Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Then in 1986 I was very exhausted by working for the film company. I was fed up with doing just commercials. I’d seen what Rose and Lucy were doing, and I’d saved up enough money to have six months doing nothing, just thinking about what I wanted to do next, so I went to work with them to set up their sponsorship and begin to think how is LIFT going to do this. Originally my work at the Festival was for three months, and then just gradually we got a little bit more money to pay for me. So that’s how I started working with them, but I actually stayed twenty years.

Do you think that thinking about sponsoring arts in a kind of marketing way as selling a product came from that experience? This is where such point of view started?

LIFT

Established in 1981, London International Festival of Theatre, has risen to become one of the most important events in the British arts scene.

I wouldn’t say it started there, but I had some expertise in enabling the two worlds to talk to one another, but it was much more a general thing in the culture and economy, so it wasn’t just me initiating this. It was more a general logic in the whole field of culture in the UK. We weren’t the only organisation doing that.

In Poland it seems almost revolutionary that you would think of getting a sponsor as if you were trying to gain a client. Going to him trying to sell something instead of asking for money.

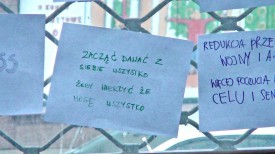

The changes,

The changes,

Julia Rowntree workshop, photo A. SlodownikThis is exactly the approach. At the beginning of course it wasn’t like going to a company as if you were a graphic designer offering a service. It was unusual for us too. But as this relationship evolved and greater understanding on both sides grew, a language did evolve through which you could speak about it. It’s true to say that one can’t do it alone. One can’t change the psychology alone. I think there are some structural things and a culture shift at a national level that can foster a greater understanding about sponsorship of the arts in Poland as a whole. For example LIFT was in touch with an organisation called the Association for Business Sponsorship of the Arts and this was very useful in lobbying government to come up with for example a scheme for encouraging business sponsors of the arts but also in setting the norms and the standards of sponsorship more generally. So that it’s unacceptable in UK terms in the arts to have a logo anywhere near the theatre or concert stage. ABSA helped to set boundaries. Even so, when you were speaking to a sponsor, you were on your own in any particular relationship.

This partly answers the question “What can art learn from business?”, like learning a different approach, different language, and the other way around: businessmen can learn the standards from art people. They can learn that there are boundaries that cannot be crossed. Could you elaborate on what else can the business world learn from the arts?

There’s a lot, but I think it’s very easy to forget that a business, just like a public sector organisation or any arts organisation has a role and a purpose, but it is also a community of humans trying to do something together. What I should emphasize is that art can help build a community of humans. If human beings trust one another, then it is easier to do whatever you have to do. The arts speak to people as human beings. You can’t go as a representative of this or that company to respond to an amazing piece of theatre, amazing painting, or a piece of music. You can only respond as a human being. And a shared experience of the arts can help build communication and trust.

This raises the question: what is really the goal of fundraising? It seems like it’s not about money anymore, but introducing a certain philosophy, and the responsibility is on the arts people side. Same with the division that we maintain between higher culture and popculture, arts vs. business, tending to think the former are better than the latter, whereas we all have the same needs.

There are two things. Before public funding, the arts always had to find patrons, unless it was folk art that was created by people spontaneously. The need for art to look for money means that you have somebody making connections with people in power. In terms of our theatre traditions it is a real tradition in our culture, that theatre brings people together across class, financial background, and it has a role in speaking truth to power. So, what if the person in society who is responsible for making connections with people in power to help them resource this social dynamic that brings people together is in fact a fundraiser. In human adaptation terms there is a traditional role for this person to play in an anthropological sense regardless of professional definition, but as a dimension of human adaptation. I find it very very interesting indeed to think of that role not primarily as looking for money, but as “OK- looking-for-money”, but actually fulfilling an ancient social role of enabling those in power to resource cultural adaptation and illumination of many other people, including themselves.

Nemawashi

[from Wikipedia] - in Japanese means an informal process of quietly laying the foundation for some proposed change or project, by talking to the people concerned, gathering support and feedback, and so forth. It is considered an important element in any major change, before any formal steps are taken, and successful nemawashi enables changes to be carried out with the consent of all sides. Nemawashi literally translates as “going around the roots”. Its original meaning was literal: digging around the roots of a tree, to prepare it for a transplant. Nemawashi is often cited as an example of a Japanese word which is difficult to translate effectively, because it is tied so closely to Japanese culture itself, although it is often translated as “laying the groundwork”.

The other thing to add is something from Hegel, the philosopher. I’m no great scholar, but I was absolutely riveted to read a piece of Hegel that talks about the master-servant relationship. If you think of the master as the person with the money, and the servant as being the person looking for the money, it’s only the servant that can change that relationship by engaging noncompetitively with the master and changing not only his own behaviour but that of the master too. Because, if the master says “change your behaviour,” it’s still the same relationship. So it’s a deep human thing to assume one doesn’t have power, but actually you do have power. It’s a very problematic thing to say in cultures like South Africa with Apartheid, where people are repressed, because of the colour of their skin, but you could maybe say that Nelson Mandela did take that kind of approach. For me it was a moment of insight. For me what forms the way I think of that role is two things: the Hegel piece and an idea of that ancient anthropological role. If you get your ideas from the beauty and connect to the right people at the right time the choreography of fundraising changes. You move from a position of supplicant directly facing a potential donor to walking together side by side with a compelling idea in prospect and suddenly someone puts their hand in their pocket and hardly notices when they give you the money. Because what you’re saying is so compelling. You do need to do a lot of nemawashi though to get a line up of people with a level of trust where you can have those kinds of conversations.

An art of sponsoring.

It has to have integrity.

What will you say to the business people you are due to address? Do you tell them that art is important? What are the messages?

The changes,

The changes,

Julia Rowntree workshop, photo A. SlodownikI think there are direct commercial reasons for sponsoring the arts, but there are other logics for aligning themselves with art events. I aim to indicate thatother priorities might exist in their companies that are more to do with long-term issues - of innovation, adaptability, resilience, and longevity that the arts can illuminate. Encouraging them to think of adaptability and longevity as a measure of success rather than simply marketing, and to think of other areas of their company that might benefit from connecting with a cultural programme in a different way.

You said during the workshop that behind every decision of, let’s say, PR manager to sponsor an event there’s always a personal reason. What reasons have you came across?

Often it was that they played music, they went to theatre, or their spouse or children were very interested in that field, or they were absolutely passionate about one particular area of art.

You also mentioned that a fundraiser must be strong and resilient to rejection.

The changes,

The changes,

Julia Rowntree workshop, photo A. SlodownikThat’s because mostly you get “no” as an answer. But there are exceptions. Once I researched a potential sponsor for a dance commissioning scheme for the Place Theatre. I researched, and researched, and researched. I rang up a potential sponsor, and my assumption was that I make the initial contact, they might ask for a meeting, and maybe a month later they will decide to give a “yes” or “no”. The man I was speaking to said “yes” on the first phone call. Now that was such a total surprise, that I hadn’t put in place all the specifics yet, so I had to say “Oh, I’ll get back to you about that.” You have to be prepared for success occasionally. I was so used to being prepared for rejection or lengthy negotiation that it was a real surprise to me. It was a lesson: prepare for success.

What do you do now?

I left LIFT in 2006, and I’ve had a lot of family affairs to organise. Now I’m doing a project very close to my heart, which is about how the knowledge of hands or making things is transmitted from one generation to the next: I am working with clay and ceramics. I’m working with a potterand we’re connecting with every country to be represented in the London Olympic Games and encouraging people from different walks of life to literally dig a kilo of clay from that country and relay the clay to London, which is built on clay. We want the world’s earth to meet London’s earth. We’re also digging clay in London with young people and teaching them ceramic skills, and working through theatre and dance and storytelling. Taking the clay out of the art room in order to put it back in. Lots of clay classes are closing everywhere, even at the university level clay departments are closing. People are losing the skill of working with their hands. We started with a little experiment, funded by the Economist Group and another private foundation, working with a school for deaf children. I’ve raised money and we’ve introduced a kiln to that school. Now they have a huge clay department.

Project Clay at Oak Lodge School from David Walker on Vimeo.

I was given some clay from Lublin last month, but the aim is to create a new public space in London that incorporates the worlds’ earths and each clay piece that comes, comes with a story. Many cultures have legends that involve clay, and so then we use these legends to teach the young people storytelling. So also calling on clay as a medium for communication. From the earliest inscribed tablets to now the silicon chip that has, at atomic level, ingredients shared with clay, we rely on clay more then we think.