Alan Lockwood: Did TR Warszawa contact you to translate the first play?

Benjamin Paloff: To the best of my recollection, they contacted me. I’d been translating Dorota’s work since her first novel. I did her first novel, she liked the translation, then I did the play. As far as I recall, it was something that had been arranged by Agata Grenda at the Polish Cultural Institute, who’s a big fan of Dorota’s work.

I’m a big fan of Agata’s work…

Yeah, me too. I think she’s really marvelous.

She leaves New York City this year, when her diplomatic cycle ends.

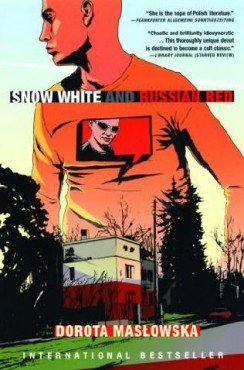

Snow White and Russian Red, translated

Snow White and Russian Red, translated

by Benjamin Paloff, Grove Press, 2005

I know, and that’s actually a big loss. She really understands how to get things done, and how to move at a productive pace without being aggressive. She pulled me on when I did the play translation for the PEN World Voices festival [in 2005], a staged reading with professional actors at CUNY [City University of New York]. Dorota was there, and we did a Q&A with her and me. Then the play was picked up for an anthology of contemporary Polish drama; the editor is a young theatre and film scholar, Adriana Prodeus. [Eat the Heart of Your Enemy is being completed by Dominika Laster, and is out later this year on Seagull Books.] She gathered a bunch of contemporary Polish plays. This was before Dorota produced the second play.

Między Nami Dobrze Jest.

Exactly. I’ve done other work by Dorota as well.

Other work meaning what?

She did an essay originally for a German or Czech anthology, German I believe [“Far Away, So Gross”]. It was a collection of essays reflecting on the transition to capitalism in the early ’90s and the early part of this century. I translated that for the anthology from Open Letter, edited by Words Without Borders, called The Wall In My Head. It’s a really funny essay, and I think it’s really smart. It touches on a lot of the problems that come up in dealing with contemporary literature from Central Europe. The author is always being asked for their—we have, in this country especially, an obsession with the Cold War. So Dorota reflects on a bunch of things, but among other things she’s reflecting on this weird phenomenon of being still a very young woman who comes to western countries and is constantly being asked, “What are your recollections of communism?” She was born in 1983, she doesn’t really have recollections of communism. At first she describes the way that she actually makes things up, because people want a tale of woe. Then she reflects more seriously on how she does remember communism, which she says she remembers strictly as an aesthetic category. She remembers colours, and the flavors and the smells, but she doesn’t really remember it as a way of life. It’s to my mind a very succinct and smart piece.

In Polish publishing, especially after someone has even a modest reputation — and she doesn’t have a modest reputation, she has a ginormous reputation — it’s common to be able to publish just about anything. It’s a much more relaxed editorial environment than we have here. After her first book she wrote a lot of columns, feuilleton, that were quick and breezy. I remember going into a reading for her second novel, before it had been published. She gave a reading from the manuscript. I went with a friend who’s an editor and critic in Kraków, we went in frankly with modest expectations. I didn’t really know Dorota at that point, and there had already been speculation that this was a one-hit wonder, phenom type thing. We went into this reading, no one had seen any of this before, and it was absolutely jaw-dropping. I think the expectation was that the reading would have connection to these things that had appeared after the first novel, in magazines, these feuilliton. Instead, what she was reading from was Queen’s Peacock, which is an extraordinary book, which deserves to be read in English if it ever materializes.

What success Grove had with your translation, Snow White and Russian Red?

How do you measure success?

Fair enough…I ask with the thought in mind that the second novel deserves its turn in English. I don’t know it, but I’ve seen her second play, which comes to an appropriately devastating conclusion.

It’s really fantastic play. I’ve translated portions of that play, as well as of Queen’s Peacock. Amy Hundley was the editor at Grove for the first novel, a very smart reader, very supportive of this type of work. As a rule, it’s unviable for a commercial publishing house. Which is true in general of contemporary literary fiction in translation. These projects are usually pet projects of individual editors. I gave Amy the sample of Queen’s Peacock and she was very enthusiastic, but for commercial reasons it was not viable. I will eventually push that along, it’s a fascinating book, very bizarre and in many ways a unique project.

You’ve been quoted saying that her work bears comparison to that of Witold Gombrowicz. Being an ardent admirer — or infected party — when it comes to Gombrowicz’s writing, I wonder if you’d expound on that.

Gombrowicz is one of the most philosophically consistent authors I’ve ever worked on or with. One of the things that comes across in Gombrowicz from the get-go, from the writing that emerges from the earliest part of his career until his death, is that there is very often a seamless marriage of language play and deeply insightful, self-consistent philosophical argumentation. He’s one of those writers for whom the medium really is the message.

I want to add before we say goodbye how excited the director Paul Bargetto is to be working from your translation for the production he’s at work on. He said outlandishly enthusiastic things; he really lit up when it came to that point.

I find lots of things very impressive about Dorota as a writer, and as a person. One of the things I find most impressive, if not awe-inspiring, is that she has a kind of preternatural gift for hearing all kinds of language and then making them glue together in a single utterance. She does this in her fiction and she does this in her plays as well, where we giggle because there’s a mash-up, grey album quality to hearing political sloganeering and street lingo in the same utterance. She marries them together in a way that tells us a lot about what they do have in common.

She also does that with personalities. In her work, there tends to be not a lot of plot. There’s emotional play in language between these characters. That’s what makes them reliable. We cannot just see, we can hear ourselves in them. She does it very whimsically. I think that’s something that’s very hard to teach. It’s like someone having perfect pitch, only for her it’s a kind of perfect pitch for language. Talented writers can train themselves in this to an extent. But for her it seems to come absolutely naturally. She’s one of the people I’ve ever met, if not the only person, who seems simultaneously entirely sane and entirely without affectation. Even when she’s doing a Q&A, if someone asks a question that she finds overly simple or impertinent, she’ll just say, Yeah, that’s not a question that interests me. She doesn’t mean to be rude; she’s simply being direct and honest with what she’s thinking.