JAKUB SOCHA: As the credits were rolling at the end of Daas, the gentleman next to me stood up, visibly upset, and yelled out, “Who the fuck is Adrian Panek”. Well, who is he?

ADRIAN PANEK: I’m a director, and this was my début. I had done a few other things before, some bigger, some smaller, so you could say I’ve become a director. I’ve always liked the idea of being a director, but I thought that I should have a specific profession, so I decided to pursue a degree in architecture first.

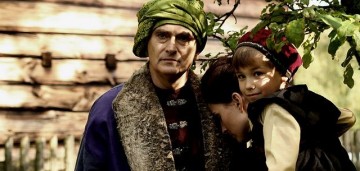

Andrzej Chyra and Adrian Panek

Andrzej Chyra and Adrian Panek

on the set of Daas

I happened to graduate from film school when the Polish Film Institute (PISF) was founded, saving my generation from ending up in a black hole like the directors that started out in the 90s. The PISF made it possible for me to début. So Adrian Panek is grateful.

Jim Jarmusch always says, “Don't let school get in the way of your education.” What was school like for you? Was it a place of belittlement or a place of growth?

I liked it. If you’re a writer, you don’t need to go to school to learn to write. But if you want to make movies, you need someone to give you film, cameras, and the money to pay your actors — you need all of those things. School is there so you can stumble and fall a few times; it’s a place where it’s OK to make mistakes. You have to start out by doing something you really want to do in order to reach the conclusion that it might not be that great after all. You could always go the indie route, but that’s much harder to do.

Belittlement isn’t something that you experience in school. Up until recently, we were strongly encouraged to make contemporary films. The most highly sought-after scripts were ones like this: two people, preferably young, preferably in a kitchen. Intimate stories. I wanted to take a different approach with Daas. I was able to achieve that goal thanks to the help of Filip Bajon, a director and my professor at film school. I don’t see myself as belittled or hindered by school.

After graduating, you went on to shoot short films, a handful of music videos, and quite a few TV commercials. Did working on these projects have any bearing on your feature-length work, or was it just a means of making a living?

Once you graduate film school, it’s crucial that you continue to work in the field, rather than ending up somewhere else and waiting for someone to let you make a movie. Shooting music videos and commercials is a fun, involving, and technically demanding job that doesn’t occupy my entire life. I still have time for personal projects. Being a director is a job, after all.

If I understand correctly, you’re OK with making commercials and music videos, but you draw the line at TV shows, especially the Polish variety, as that would be working for the “film factory”.

Shooting commercials can also be a “film factory” job. I’ve never been so involved in the job that I didn’t have time for anything else. In this line of work, you have to make a choice: either commercials or shows. I think only Andrzej Wajda and perhaps a handful of other directors can make a living off of filmmaking alone.

What did you get out of the Polish Film Festival in Gdynia?

My film was the first one screened at the festival, and it received plenty of reviews, most of which made me very happy. My name has become more recognizable: when people hear Panek, they either think of that good movie, or that weird one.

While many have praised your film, some critics have expressed their disappointment, saying that you had a shot at Jacob Frank — a Jewish mystic and a fascinating character — and you didn’t put him in the centre of your story; you didn’t fulfil their expectations of a biopic.

Jacob Frank was, above all else, a scandalous figure. All those practices that stemmed from the Manichean themes, the orgies, the provoking of the rabbis, the political games with the clergy and the authorities — people think this is the real subject of the film. My impression, on the other hand, is that there are plenty of movies about figures whose lives were one big game. Making a film about such a scandalous character living in 19th-century Poland just seemed unnecessarily tautological. Frank is so ambiguous that every viewer will see their own topic in him: for some he’ll be the first atheist, for others: the first revolutionary, while others will see him as the devil. What mattered to me was that Frank believed himself to be the messiah. That’s a completely different code. What I find most moving in the Frankists is a need that has always existed in man — the expectation of a different dimension of reality, the desire to place a map over it that would explain it to us, reassure us, or tell us that reality is not what it appears to be. That map doesn’t have to be religion: it could just as well be Marxism or any other ideology.

The more crucial matter with such characters as Frank is that you need to create a hero who is a god. So you can’t show him in the first person, as he eats, sleeps, and has doubts. God doesn’t do that: he is a venerated being who acts through others. A first-person character is, by definition, human and has all the attributes that humans share, such as physiology. It seemed appropriate to depict Frank through the eyes of Goliński and Klein. A divine figure, or one who claims to be god, operates through the effect he has on others, rather than who he actually is. Frank is the central character in Daas, but in a different way.

But there are numerous moments in the film where reality is warped, and there are several magical elements that are closely tied to Frank. Weren’t you afraid of turning the whole movie into a fairy tale, something completely fantastic?

There’s not too much of that in the film. In fact, there are only two such elements, both of which can be explained rationally as effects of Klein’s breakdown or his wife’s momentary return to health. That’s exactly what Frank did: some saw in his actions as purely charismatic, others saw a true gift in them.

Viewers of your film are also confused by the lack of context. There is a screen introducing the world in which the movie takes place, but it is rather vague. Weren’t you concerned that that would be insufficient?

The plot itself doesn’t really have that much potential. If you focus too much on the historical and social circumstances that defined the period, you’ll end up with nothing more than a description, something along the lines of a documentary that merely states the facts.

But there’s a different issue here: not even Jacob Frank experts are sure about the meaning of some the gestures performed by him and his followers. They would brush coins aside with their bare feet and imitate animal calls — no one knows what to make of that, as no explanations have survived to this day. I talked to Jan Doktór, a specialist in the field, who told me he suspected they were some kind of vestiges of states of enlightenment that Frank had experienced, or thought he had experienced. All of these issues remain a mystery, and it’s true that when you make a movie about mysterious and enigmatic things, your entire film becomes mysterious and enigmatic. But that’s precisely what this film’s about: all we can do is project our interpretations onto into.

To me, the key character of the film is Joseph II, who represents a content man who has risen above all the goals and ideals that propel others onward. He is the victor. Klein and Goliński attempt to free themselves of his power; we see them waiting to board a ship to a better world. It’s a bitter and ironic image — we know that there is no better world for them. Writing about Frank, Scholem said that he had stripped mysticism of its mysticism, and that he was a nihilist who was interested in nothing more than power.

We don’t really know what’s what in today’s times. On the one hand, you have the strong influence of religion: we’re involved in a religious war in the Middle East. On the other hand, there’s the powerful force of science, which has allowed us to live longer than before. All of these things emerged in the 18th century, and they’re still with us today and have not lost relevance. And yet this better world can still come about — not because it’s socially feasible, but because it’s an immanent need of mankind. That’s what matters to me.

Themes such as liminal situations and excursions beyond the rational order of things appeared in your earlier work, for instance in your short film My Poor Head. Don’t you think that such topics are destined to fail right from the start? After all, you take the perspective of a healthy person, one that can rationalise everything.

I find it interesting that we have a certain image of reality, and then something suddenly comes along and tears that image down and changes our lives. There’s another explanation for this interest of mine: it’s the very nature of film to portray things that are uncanny. It’s no accident that script-writing guides always tell you to portray reality, but cut the boring parts out.

I had a clear idea of what it was I wanted to do, but I was curious how others saw it. As a director, it’s part of my job not to know certain things. A director isn’t someone who just stands at the bridge and shouts out orders. A film is something that happens between people, something that’s alive. I really like that community.

Do you try to avoid the influence of others? Someone say that Bajon made this movie for you.

The way Filip Bajon works is he tells you what he likes and what he doesn’t like. That’s where his interference ends. But when I was choosing which film school to go to, one of the things that drew me to Katowice was the fact that Bajon taught there. I had seen his film Inspection of the Crime Scene 1901, which was ostensibly the story of the strike in Września, but actually told a different, extraordinary tale. I’m glad to have studied under Bajon, but I studied under other directors as well.

Wojciech Has was another name often mentioned in reviews of Daas.

That’s great. I’m happy that my movie reminds people of films by Bajon and Has. I take that as a compliment.

Do you absorb outside influences, or do you try to keep your head clear and unpolluted?

Freedom from influence is a utopian concept. I once heard that when Krzysztof Komeda found it too easy to write music, he would ask a trusted friend whether he had committed plagiarism. I make a point of watching movies and reading, if only to avoid reinventing the wheel. There’s also a certain amount of technique involved in filmmaking, and watching movies gives me a chance to learn a few tricks from others. Keeping a clear head means keeping perspective: if you don’t treat yourself as the font of all knowledge, you stand a chance of producing some interesting work.

translated by Arthur Barys