The mountain of literature on the topic of today’s child soldiers is piled high, particularly in the aftermath of the Kony 2012 video produced earlier this year by the Invisible Children organisation, which called for the world to pledge money to fund the pursuit and capture of the man behind the most ruthless army of children in the world – the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) of Uganda. Within 72 hours of the film’s Youtube release, 43 million people saw the story and were moved by the drive to stop the injustice, spurred on by celebrity endorsement from some of the biggest stars in the world, from Oprah to pop stars Rihanna and Justin Bieber, George Clooney and Angelina Jolie. Views reached 100 million and in the meantime the video was swiftly dismissed as “misleading” and “misguided” by some of the world’s most respected media outlets. Several days later Invisible Children’s founder Jason Russell was detained by police after appearing naked and intoxicated in public on Thursday morning in March, disrupting traffic and yelling incoherently. Suddenly the world that was so hyped on the Kony 2012 ideology felt duped. Kony and the kidnapped child soldiers of the LRA were once again forgotten. The family blamed the stress of the backlash on the episode and there has been little said about what really happened to Russell that day. Some bloggers have attributed the episode to magic – a curse set upon Russell by Kony himself. That claims has, of course, been refuted in the mainstream media in favour of the more plausible argument of temporary psychosis, but the topic of witchcraft is a common one in many parts of Africa and plays a big part in the story of the LRA.

Wojciech Jagielski, The Night Wanderers.

Wojciech Jagielski, The Night Wanderers.

Uganda’s Children and the Lord’s Resistance Army,

translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Old Street Publishing,

Brecon 2012, 320 pages It is no wonder then that the power of magic takes up a hefty chunk of Wojciech Jagielski’s book The Night Wanderers, with the author wavering between belief and disbelief in magic bullets and the power of faith in making a man (or child) immortal and making him capable of butchering hundreds of innocent men, women and children – even his own parents. Jagielski, one of Poland’s most prominent international correspondents, goes deep into the heart of the conflict and takes on the subject of the spirit world and witchcraft as a matter of fact. Magic appears to lurk behind every development of this war – spiritually, historically and politically.

He travels to the Ugandan countryside, to the town of Gulu, where one of many rehabilitation centres for former child soldiers is set up. There he meets Nora, a woman who has dedicated her life to these children, and Samuel, a boy whose story he tries his best to draw out of him. Yet to no avail. If Jagielski’s aim was to tell the story of a real child soldier in Uganda, he has not accomplished it. Samuel is a shy, untrusting young man who seems terrified of his past and does not wish to retell it or share it with anyone. Ultimately, the book is rather a tale of the frustration of being a lone reporter in the heart of Africa. The tale of a writer struggling to break into the confidence of the locals of a particular place and always remaining on the fringes.

He answered every question, concisely and directly, which I took for defenseless, sincere frankness, and which made the conversation harder for me. It was I who was having trouble formulating my questions, to which, like a model student, Sam was instantly giving the answers. I just couldn’t find the right words, they all seemed inappropriate to what I wanted to ask, not the ones I needed.

A face-to-face meeting with a former child soldier must be daunting. And yet others have done it and not suffered the sort of stage fright Jagielski appears to be experiencing. There is quite enough English-language literature on the topic – from Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Child Soldier to Peter Eichstaedt’s First Kill Your Family: Child Soldiers of Uganda and many more in between – to paint a complete portrait of the desperate situation in Uganda and other African nations. Beah’s story gives a first-person insight into the mind of someone who experienced the horrors of the LRA and managed to escape and share his story with the world – but only after intensive rehabilitation, nonetheless. Peter Eichstaedt gives a thorough account of both the historical and political backdrop of the war and Kony’s engagement in it, along with thorough, incisive interviews with former and current child soldiers, some even as young as seven. Against the backdrop of the library of exhaustive texts on the subject, Jagielski’s book doesn’t bring much more to the table. While the Polish edition (published in 2009) surely provided readers in Jagielski’s own country with a familiar perspective on such a significant – yet all the while distant both geographically and culturally – subject, the English edition (published in 2012) appears rather superfluous, shedding little new light on the issue in the global forum. The translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones successfully delivers the vision of Jagielski’s experience and the troubled emotions that come with the task of the international correspondent covering such a complex issue, yet at certain points there is the impression that the translator is locked within the Polish syntax. The text is often littered with commas and dashes that break up the narrative structure, making it tough on a reader who is more accustomed to the streamlined sentences of Western reportage.

Wojciech Jagielski

Wojciech Jagielski is a reporter at Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland’s biggest independent daily, where he specialises in Africa, Central Asia, the Trans-Caucasus and the Caucasus. He has received the Dariusz Fikus Award and the Letterature dal Fronte Award (Italy) for his book Towers of Stone: The Battle of Wills in Chechnya. The Night Wanderers was shortlisted for the 2010 Nike Award, Poland’s most important literary prize.

If a reader can accept these flaws and get on with it, then an alternative reading of the book as a story of the struggle of an ambitious writer to tell a hard-cutting story in a sincere, well-researched way is almost as rewarding. Particularly given the fact that Jagielski is standing in the shadow of his hero, Ryszard Kapuściński, one of the world’s foremost writers on Africa and a fellow journalist from Poland. It is no wonder Jagielski appears to doubt himself at every turn, finding he might have bitten off more than he can chew, finding he has trouble fixing on the story he wants to tell and the story people will want to hear. Many critics have taken issue with reports that Kapuściński was known to colour his stories for heightened dramatic effect. Jagielski, on the other hand, seems stuck between trying to stick to the facts at hand and telling a compelling story without resorting to writerly tricks to build his story. It is perhaps the ensuing anxiety that creates a certain havoc within his story, which also gives it a sincere, human touch that is often lacking in the non-fiction genre.

We try to guess the readers’ and viewers’ tastes, and tailor our reports to suit them. Instead of becoming eyewitnesses to events and messengers bringing news, are we becoming a new kind of traveling salesman or court jester?

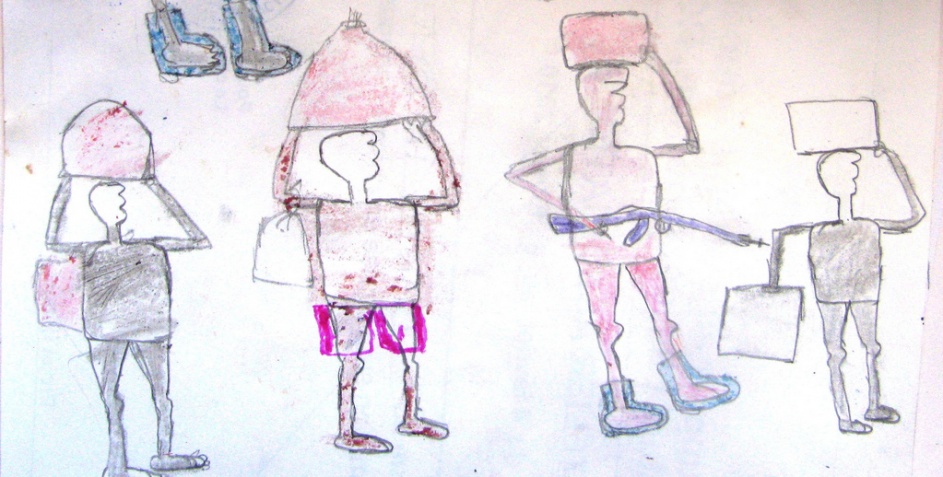

Jagielski succumbs to the trick of conjuring up an amalgam of personalities to build his main characters – a point of contention that several critical reviews of The Night Wanderers have pointed out. In the foreword he admits that “the characters of Nora, Samuel, and Jackson have been created out of several real people.” The realest of those people seems to be Nora, whose hairstyles and outfits he describes in unremitting detail, hinting perhaps at a romantic relationship between himself and the “real” Nora. At times his relationship with Samuel too appears to grow as the boy seems more willing to tell the story of how he murdered his family and set out across the country at the heels of Kony, ruthlessly bludgeoning countless numbers of innocent villagers, only to draw back into his shell without warning, just as the gruesome facts of his past start rising to the surface. Jagielski’s relatively uneventful narrative is interlaced with a choppy historical narrative of how Uganda found itself in this position, the political turmoil that set these despicable wheels in motion and how the indelible vestiges of the pan-African belief in spirits and magic create an aura of fear that keeps civilians locked in permanent terror and the rebels convinced they are virtually untouchable. It is not an action story, as many other critics have remarked, but rather an attempt to understand the situation in Uganda in a thoughtful, contemplative way. An attempt to understand how the moral fabric of Ugandan society has been destroyed, with families torn apart, children kidnapped and made to be killers and concubines. Those who manage to escape are feared and shunned by their families, living on the fringes of society, they wander the night alone, cut off from society forever. They are constantly on the run, hiding beneath the cover of night and vanishing in the morning, painfully aware that if they are caught by the LRA, their desertion will have earned them a gruesome punishment. These children have almost no one to turn to, save a few charitable individuals like Nora.

The people in Jagielski’s book seem to shift between a conviction that the spirit world is indeed at work here, giving Kony the power to wreak such havoc in Uganda and beyond, and a mocking incredulity that anyone would ever believe in such nonsense. And yet from the very beginning Jagielski seems to believe in these spirits and indulges in this belief, using the invocation and possession of such spirits as the basis for Uganda’s recent history. The narrative takes a sharp dramatic turn as he pays a visit to the house of Severino, the father of Alice of the Holy Spirit (the first incarnation of the war-hungry spirit Lakwena who almost single-handedly initiated the bloody conflict, also a relative of Kony’s). There Jagielski witnesses the spirit of Lakwena entering the body of the old man who blurts out a bunch of pseudo-religious ideology about sin, guilt, judgment, victory and vengeance. What should ultimately be a turning point for Jagielski’s spirit-infused tale, ultimately falls to an anti-climactic low and the story ends with no real answers, no tangible conclusions. All we are left with is an impression of how Uganda has suffered, caught between a web of political machinations that spread across the globe as world leaders turn a blind eye to the conflict and injustice, while arms dealers continue to provide Kony and his child killers with ammunition to continue to destroy families and the cultural fabric of this African nation. All we are left with is a profound feeling of sadness and frustration.